DADA and Black Metal – An Essay on Art and Music

DADA and Black Metal

Introduction

This essay is to compare and contrast the anti-Art movement of Dada with the musical genre of Black Metal. This may seem bizarre to begin with, but by taking a look into the ideology behind the music and the ideology of Dada, I’m hoping a deeper understanding of Black Metal can be attempted. Black Metal has been the subject of some controversy. If not for the violent crimes associated with the genre or it’s connection with Satanism. Then perhaps the reasons for it’s existence and why it resonates with so many people and to this day – it could be described as a cultural phenomenon. Dada would appear, on the surface, very different. What has Art or more accurately anti-Art got to do with Black Metal? Well, first I shall attempt to offer a definition as to the ethos of Dada and then Black Metal respectively. Then through comparing and contrast I’ll go into some specific aspects of both in hopes to give light of some similarities. This may position some theories as to why Black Metal is so passionately loved and defended by some people and completely misunderstood by others.

What is Dada?

A definition of Dada that I find useful is that which is summarised here:

“[Dada is a] Nihilistic movement in the arts. It originated in Zürich, Switz., in 1916 and flourished in New York City, Paris, and the German cities of Berlin, Cologne, and Hannover in the early 20th century. The name, French for “hobbyhorse,” was selected by a chance procedure and adopted by a group of artists, including Jean Arp, Marcel Duchamp, Man Ray, and Francis Picabia, to symbolize their emphasis on the illogical and absurd. The movement grew out of disgust with bourgeois values and despair over World War I. The archetypal Dada forms of expression were the nonsense poem and the ready-made”[1]

So at the turn of the 20th Century Dada was embraced by many artists around Europe and New York amidst the first World War. This position shows that this phenomenon was something cross cultural but also it gives a reason for the anger the artists felt. These artists were disgusted with society for allowing the war to happen and they saw that the logic, that civilised society fiercely adhered to, as one of the key causes.

“Thus DADA was born, out of a need for independence, out of mistrust for the community. People who join us keep their freedom. We don’t accept any theories. We’ve had enough of the cubist and futurist academies: laboratories of formal ideas. Do we make art in order to earn money and keep the dear bourgeoisie happy? Rhymes have the smack of money, and inflexion slides along the line of the stomach in profile.”[2]

Dada was defined by an idea to reject. Art had become a way of selling to the highest bidder the bourgeois idea of good taste. So we have with The Fountain (Marcel Duchamp, 1917, Figure 1.) an object that is far from an articulated painting. “The story is well known: Duchamp, under the alias R. Mutt, submitted an inverted urinal; the hanging committee refused to show it; the object was “hidden” behind a partition; and Duchamp and Walter Arensberg resigned in protest.”[3] It is an object that is part of the every day but also part of a private matter. The act of urination is something not to be associated with art and therefore by presenting it as art it is essentially an insult.

“Oddly enough in the face of the “No Jury, No Prizes” slogan, [the judges] employ the rhetoric of taste to justify their refusal to legitimate The Fountain as art. (…) [For one of the judges who objected] the urinal was a tasteless object, an affront to bourgeois propriety and sensibility. “It is indecent!” he roared upon seeing it for the first time.”[4]

Thus The Fountain became one of the most infamous example of Dada at work. Dada is employed to represent the artists distaste with society – seen as the bourgeoisie. The idea of the ready-made shows a move towards art that isn’t representing ‘good taste’. Rather than the talented painters that were seen by the Dadaists to be just out to make money.

Another famous example of Dada is the Karawane (Hugo Ball, 1916) which was a sound poem that had no recognisable (or at least ambiguous) words. “As one commentator describes it, “Ball’s lautgedichte [Editor: translates as sound poetry] convey the physical substance of sound, sound as gutteral rumblings, sound as voice, generated by lungs, larynx, vocal chords, tongue, and lips, producing sudden trills and sibilations.”[5] This reflects yet another way that an art form has been deconstructed as the words become mere sounds.

Dada is a broad and detailed subject and to argue it’s specific nature and properties is beyond the scope of this essay, however, it is important to recognise it’s apparent need to reject bourgeois society. This was also done in many ways that embraced the illogical, the absurd, things by chance as well as outright mockery. This was part of the important ethos behind Dada.

Heavy Metal and Black Metal

“You know what the devil’s best trick is, it’s making people believe he’s a joke. That he doesn’t exist. As a christian I totally believe he exists. I totally believe that’s his best weapon. So I expose- You know on a satanic thing. I expose Satan. I’m not trying to be him. You know if you study theology and you really are involved in this theology you realise that satan doesn’t have points on his head, he doesn’t have a tail. Satan is the greatest car salesman on the planet. He is so good at selling to you and he’s- You’re never going to recognise him. He’s the sweetest guy, he’s your best friend. He would never do anything to hurt you. Just come on. You know he’s that guy he’s not [Editors Note: Alice Cooper makes horns with his fist] that guy. That’s the joke there. The guy that you want to watch out for is the guy that comes off as being your best friend. Oh I refer to Alice in the third person. I play Alice I don’t live Alice. (…) He’s not human he doesn’t belong in this realm.”[6]

Here, Alice Cooper highlights some of the key ideas that I’d like to address. Black Metal is a music genre within Metal. Metal, as Alice Cooper points out, is quite theatrical. Alice Cooper isn’t Satan but does play to a character. The horns that have become an important part of Metal and is commonly associated with Satan[7], are more like the leather of bad boys – It’s a look, or as Alice Cooper says a joke. That isn’t to say that it doesn’t have a dark nature to it. Metal is still interested in Satan or being ‘evil’. In giving the horns that is associated with Satan there is the expression of that interest. Black Sabbath’s first album Black Sabbath (Black Sabbath, Regent Sound Studios UK 1970, Figure 2.) offers some of the most defining aspects of what Metal is. The album’s sound was a:

“sonic ugliness reflecting the bleak industrial nightmare of Birmingham (…) [and] thematically, most of heavy metal’s great lyrical obsessions are not only here, they’re all crammed onto side one. “Black Sabbath,” “The Wizard,” “Behind the Wall of Sleep,” and “N.I.B.” evoke visions of evil, paganism, and the occult as filtered through horror films and the writings of J.R.R. Tolkien, H.P. Lovecraft, and Dennis Wheatley.”[8]

Metal is preoccupied with darkness, horror, death and evil. There may be many reasons for this that are, again, beyond the scope of this essay but this would appear to trace back to it’s very origins (arguably with Black Sabbath[9]). This is important to recognise as with Black Metal you see a sense with which this interest has only increased. This idea has been further elaborated on by Shining frontman Jørgen Munkeby in his article: “Less is bore; The Ever Upward Spiral in Intensity” but for now, he gives us the idea that “From less to more, from consonance to dissonance. Today’s harsh music, will be tomorrow’s boring background music.”[10] With this in mind we can view how (to over simplify it) Heavy Metal goes to Thrash Metal and then to Black Metal. It would be far too simple (and reductionist) to say that Black Metal is like Heavy Metal but more, but there is that important connection.

What is Black Metal?

“In issue #2 of ours, Count Grishnackh said that the “Only true bands from Norway” are Mayhem, Darkthrone and Burzum, the others are just stupid fucking children playing with things they don’t snow shit about. But if these three are the “only true ones” why does Immortal and Emperor belong in the “Norwegian Black Circle?” And what about other Norwegian bands such as Thorns, Thou Shalt Suffer, and Satyricon?

Again, Count will have to answer in his own words, I have always supported Emperor and Immortal. But we do have some fake bands here, but I’m not going to give you any names. you will eventually find out.”[11]

Here, an interview given by Euronymous of Mayhem was given by Kill Yourself! Magazine and highlights one of the key arguments in Black Metal – who actually plays Black Metal? This is slightly beyond the scope of this essay. A sense of elitism within Black Metal can be argued for and against.[12] However in the above question it is pointed out that Count Grishnackh of Burzum makes one claim as to who is included as a Black Metal band, only for Euronymous to argue that those were his words. Similarly (and usefully) a few more bands were pointed out as key Black Metal bands. So we have: Mayhem, Burzum, Darkthrone, Immortal, Emperor, Thorns, Thou Shalt Suffer and Satyricon. This essay will focus on some of these bands as part of the infamous Norwegian Black Metal Inner Circle that appears to define most of Black Metal. Despite this it is important to recognise that Black Metal like Dada wasn’t actually specific to one location, there are other bands like Enthroned from Belgium, Sigh from Japan and Behemoth from Poland, for example.

Despite the bands that are from other countries that are associated with Black Metal, common attention is given to a few bands from Norway that make up the Norwegian Black Metal inner Circle. This may well be due to the crimes associated with the bands. In 1991 Mayhem vocalist Dead committed suicide by shooting himself in the head with a shotgun.[13] In 1992 Emperor drummer Faust stabbed a guy to death apparently for a homosexual advance.[14] In 1994 Count Grishnackh killed Euronymous, they were most famous for Burzum and Mayhem respectively.[15] 1992-1994 churches were burnt and many band members were charged with the crimes.[16] These weren’t the only crimes that were committed or suicides that occurred with people who are in Black Metal bands but they are the most notable. Despite this, it isn’t within the scope of this essay to look into these crimes in more depth. The reasons behind them, everything that has happened and also whether it was the crimes or the music that caused the success of the bands aren’t the focus of this essay at all. However, these crimes are important to bear in mind as part of Black Metal’s history.

If we look to members of bands like Burzum, Darkthrone, Emperor, Immortal, Mayhem and Satyricon many of the key attributes can easily be identified in interviews with them. For example:

“Well for me, you know, black metal is a conception for the grim, dark, morbid side of metal, y’know, extreme music. And black metal first came as a conception for a Venom album which came out in 1982 so basically it comes from Venom. And I would say that if you are true to the eighties and true to the basic… you know, like many call themselves black metal bands today but I think that many of them have become more in this goth, in this gothic kind of way, but for us it’s still the feeling of the eighties, the fashion of the metal eighties with spikes, or leather, or bullet belts – we are old-fashioned. And we still think that if it’s gonna be true metal, it has to be in old fashion.”[17]

This interview with Abbath from Immortal highlights some of the key aspects and history of the genre. Despite the controversies Black Metal is about a return to this idea of earlier bands as putting across that aesthetic and feeling. The evil of Black Sabbath is a continuing part of Metal that is only all the more emphasised through Back Metal’s return to bands like Venom. Satyr of Satyricon further elaborates:

“Around 1997 one band after the other went into the gothic direction and the bands that chose to stay more brutal went into the death metal direction. It left the black metal scene in a void where the substantial bands with a certain darkness and edge were disappearing. We chose to stay in black metal with both our feet and created something very cold, unfriendly and hostile.”[18]

Again Satyr, like Abbath, describes a dark atmosphere which also is unfriendly and hostile and therefore can be seen as anti-society much like Dada. This being a key aspect of Black Metal. Another important part to note is that again bands are referred to as moving away from Black Metal into Death Metal and Goth, this infers elitism but doesn’t necessitate it. Black Metal merely is attempting to define itself as apart from these genres in a nostalgic throwback to the feeling that Abbath refers to when he says ‘we are old-fashioned’. Ihsahn of Emperor continues:

“As I have said before, I feel Black Metal should have nothing to do with politics. It’s not a political thing, it’s something more spiritual. I realise that many people think that Fascism, Satanism and Black Metal are one and the same, probably because they are all extreme ideologies.”[19]

Ihsahn importantly clarifies that Black Metal does not actually equate to Satanism or Fascism. The Satanism that can be interpreted as a part of Black Metal is much like the joke that Alice Cooper referred to earlier and also that dark and morbid interest that Satyr and Abbath spoke of. With all of this in mind Satyr offers the best clarification of what Black Metal is when he said:

“The most important thing to understand, if you are trying to learn what the essence in what black metal is about, is it’s essentially defined by a feeling. It’s not how the logo looks, not the production, although that can be an element, and not necessarily the speed. You can suggest that, in general, black metal tends to be more atmospheric than say death metal, but I think first and foremost black metal is about a certain feeling. Whether a band looks a certain way or not, that’s not really the most important thing nor their lyrical themes, it’s the feeling. How to detect that? You just either get it or you don’t.”[20]

This feeling, as unfortunately ambiguous as it is, is the defining element of Black Metal. Based upon this dark, cold, grim and hostile idea that infuses Black Metal with a very anti-society attitude. This actually being a similar trait to a key characteristic of Dada and our first major similarity. Dada as we saw angrily expressed the idea to reject and destroy bourgeois society but was also “a state of mind”[21] as André Breton says. Black Metal is as Gaahl of Gorgoroth fame states: “Black metal is a war against what everyone knows.”[22] This opposition is often represented by, but isn’t restricted to, Satanism.

Black Metal and Dada

“How can one get rid of everything that smacks of journalism, worms, everything nice and right, blinkered, moralistic, europeanised, enervated? By saying dada.”[23] In the period when Dada was very active the Dadaists very much believed that Dada could destroy what was known and it would be a valid affront to society. “A sculpture by [Max] Ernst had an axe attached with which the audience were invited to destroy it.”[24] This very emphasis on destruction just shows how far they were willing to go. Though now they may not be seen as a particularly violent movement, back then there was a real sense of anger with established society. Ironically this sense of destruction targeted a society that included Dada and therefore “in a sense Dada existed in order to destroy itself.”[25] Black Metal is also anti-society and many never thought of any sort of success in fact they also opposed it.

“The idea with Burzum was not only to make original and personal music, but also to create something new – a “darkness” in a far too “light”, safe and boring world. Unlike 99% of all musicians I didn’t play music to become famous, earn money and get laid. I had no interest in neither fame nor money.”[26]

Count Grishnackh of Burzum describes his attitude to music as being about the creation itself and not to get it out to the masses at all. Similarly Emperor disbanded at a point in their career when they felt Emperor could become compromised by success. “The reason I left Emperor in the first place was because I felt that there were so many opinions of what Emperor should or should not be. It was effecting my creativity and I wanted to do something else.”[27] Here Ihsahn very clearly points out that Emperor had become something bigger than what they were hoping it would. This built to many people to expect certain things from Emperor rather than leaving with them that sense of freedom. This may not make sense to many, a band disbanding because of success but for Black Metal it makes perfect sense. This also represents a sense in which Black Metal, like Dada, existed to destroy itself.

This idea was also tied up with Black Metal’s anti commercialist attitude. “I refuse to have anything to do with any of the mainstream trendies in the scene today”[28] here Euronymous criticises the then modern metal scene for becoming trendy and by extension a popular scene in itself. This attitude is a large part of the ethos and has also been associated with the idea of elitism within black metal. In fact Ihsahn makes a useful comment here: “As soon as the black metal thing turned into conformity, I think that triggered my opposition. My opposition to conformity is what brought me to black metal in the first place.”[29] Black Metal is opposed to society and culture and therefore it makes sense that Black Metal musicians would be against being commercial, trendy and conforming. This idea is infused into a lot of what Black Metal musicians do, such as: low production values; rasped/hard to hear vocals; alias’; and indecipherable logos. Dada in being against the bourgeois society and the commercialised nature of Art (as earlier asked by Tristan Tzara: ‘Do we make art in order to earn money and keep the dear bourgeoisie happy’) at the time shows a similar ethos.

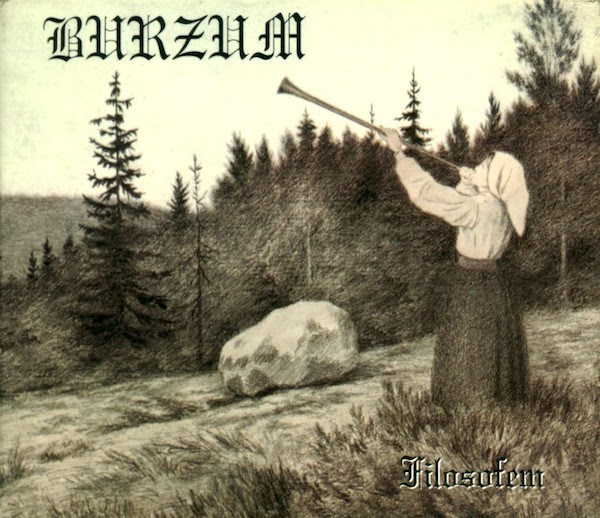

If we look at album’s like Burzum’s Filosofem (Burzum, Misanthropy, 1996, Figure 4.) and Darkthrone’s Transilvanian Hunger (Darkthrone, Peaceville, 1994, Figure 3.) we can see examples of this low-fi buzz-saw like production values for. “The natural and best music is (as I see it) music with “soul”, and not music that has been polished for months in a studio to remove even the tiniest mistakes (peculiarities).”[30]. This could be compared to an idea in Dada best represented by their love of primitivism. The Baroness Elsa Von Freytag Loringhoven was described as: “The first American dada… [and the] only one living anywhere who dresses dada, loves dada, lives dada.”[31] She was someone who’s behaviour and works demonstrated Dada, for example:

“As an oxymoronic European barbarian herself, the Baroness fetishized objects in the ‘primitive’ sense – collecting things viewed as detritus by ‘civilised’ people and refashioning them into something of immense personal value. At the same time, through aggressive and publicly enacted sexual behaviour and excessive flamboyant self-display, she refused the modern fetishizing effects of the capitalist, patriarchal ‘gaze’”[32]

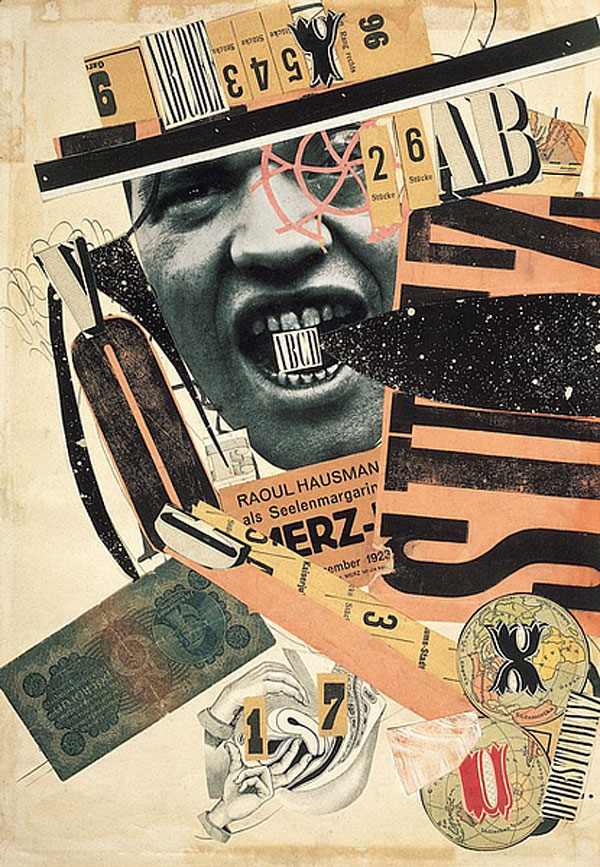

Here The Baroness demonstrates what Dada saw in primitivism and this further elaborates on what Marcel Duchamp’s The Fountain did against Art in 1917. Their aggressive stance against the bourgeoisie managed to offend them by taking them back to their primitive or carnal roots. Further to this works of Dada such as ABCD (Raoul Hausmann, Collage, 1920, Figure 7.) quite literally shows other works being cut up to form new works of Dada. As such “They draw the viewer’s attention to art’s grasp on reality, encouraging so much scepticism about established pictorial conventions that these are completely rejected: ‘The end of painting and its methods is acknowledged’”[33] This was another way they attempted to destroy the established order of Art and were deeply opposed to the commercial aspects of what Art was. They literally challenged ideas of good taste. This could also be said of Black Metal who went against what was seen as ‘good production’.

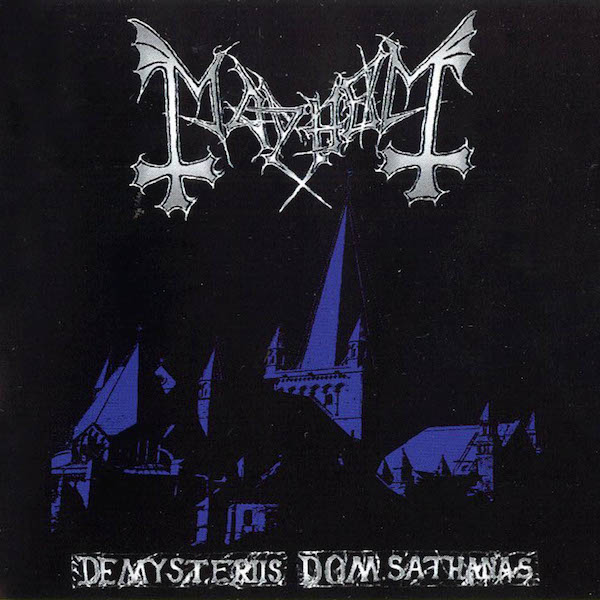

The sound of a Black Metal vocalist is quite distinct to the genre and if we look to album’s like Satyricon’s Nemesis Divina (Satyricon, Moonfog, 1996) or perhaps Mayhem’s De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas (Mayhem, Deathlike Silence, 1994, Figure 9.) or Emperor’s In the Nightside Eclipse (Emperor, Candlelight, 1994, Figure 5.), we hear a style of vocals that are akin to shrieks, guttural rasped singing and generally indistinguishable vocals. If we also look to Hugo Ball’s sound poems like the aforementioned Karawane we can see a similar destruction of words in poetry to Black Metal’s destruction of words in song.

“As such, it was symptomatic of what Sigmund Freud diagnosed as the speech of the traumatized subject of brutal combat, plagued by a compulsion for repetition in which comprehension and experience were mutually exclusive. (…) While Ball’s poetry implies trauma, expressed through speech, it is also marked by a “senselessness” that reflects an expressive incapacity. The inability to communicate suggests that warfare had left us poorer – not richer – in communicable experience, as Walter Benjamin observed. Rather than producing stories to tell, warfare had crippled language.”[34]

If Hugo Ball’s poetry had crippled language then surely the Black Metal Shriek had done something similar in reducing the words to a sound – an aggressive sound. The sounds were very different, given that Hugo Ball’s poetry was a more literal destruction of the word, as they have no clear meanings, but the ethos is the same and they both leave the listener confused as to what they just heard.

We have already heard words from Ihsahn of Emperor, Count Grishnakh of Burzum, Euronymous of Mayhem and Satyr of Satyricon – sufficed to say that these aren’t their birth names. Say what you like about their alias’ they did again represent the same values evident already in Black Metal. Count Grishnakh comments:

“If people knew that Burzum was just the band of some teenager that would sort of ruin the magic, I figured, and for that reason I felt that I needed to be anonymous. So I used a pseudonym, Count Grishnackh, and used a photo of me that didn’t look like me at all, on the debut album, to make Burzum itself seem more out-of-this world, and to confuse people”[35]

The alias exists to give a certain anonymity to Burzum and keep its magic alive, whilst also keeping the attitude of against society as, rather than to inform fans, it confuses them. If we were to also look at the typical Black Metal logo exemplified by Darkthrone’s Transilvanian Hunger we can see an effort to confuse and make unreadable the readable. You have to really know the band to know their logo. This similar to the undecipherable vocals and alias’, exists as a critique on society values and the commercial idea of music. Furthermore a band name or artist’s name and by extension their logo exist as a trademark. Now, if we were to return again to Marcel Duchamp’s The Fountain we can see a critique of the idea of a trademark.

Rrose Sélavy (Marcel Duchamp, 1921 (photograph by Man Ray), Figure 8.) (Man Ray photographs Marcel Duchamp in another alias: Rrose Selavy (sometimes Rose Selavy), which acts much like R. Mutt but is more developed here.)

“He manipulated the idea of the trademark by signing the urinal with a new ‘trademark’, R. Mutt. Yet R. Mutt is not your average trademark; it is an abandonment of or affront to everything the trademark stands for. J. L. Mott, because of name recognition, may have guaranteed the authenticity of the urinal, but in its rotational transformation into an art object, R. Mutt;s signature does not guarantee much. Instead it is a joke, a visual pun on the similarity between the signature of the artist and the trademark of consumer culture. ”[36]

Marcel Duchamp again demonstrates Dada values in creating an alias and keeping himself anonymous and furthermore making fun of the whole idea of a trademark. The artist becomes a brand name and helps the commercial nature of Art – something that Dada despises. So, Dada makes this a joke and confuses those who interpret his work of Dada. This is again achieved by Black Metal in their way of confusing the logo and also giving such an alias. This is a striking similarity but admittedly unlikely a direct influence.

Conclusion

In looking at such ideas we can see some striking similarities but also some stark contrasts. Black Metal takes the aggressive stance of Heavy Metal and uses a critique of good taste as the ugly or evil to make fun of established ideas of what is acceptable or what is even music. The grim and dark nature of the music shows a very big difference to Dada that, despite being very aggressive, isn’t nearly as dark. Also, though Dada exists to critique the bourgeoisie and society as whole, which does include established religion, they don’t take it to an idea of Satanism which can be seen in most Black Metal. The similarities, I hope I have demonstrated, are quite numerous and quite informing. In looking at Dada with regards to Black Metal we can see a similar anti-society attitude which gives meaning to a lot of the key elements of the musical genre. Black Metal is non-society; it is “a war against what everyone knows.”[37] The ways in which it does this seem akin to Dada, confusing the role of the artist, making ugly and aggressive the very forms of creation it takes. They are both very much against established society but in slightly different ways.

Also, despite what this can tell us about Black Metal we have to bear in mind that many Black Metal musicians argue over who should be considered a part of Black Metal and what defines Black Metal. Satyr and Abbath describe Black Metal as dark and cold and not necessarily Satanic, but musicians like Euronymous say it is about Satan and Death. This might be a metaphor for the anti-society stance that Black Metal takes but it may not. Also, Count Grishnakh was quoted as saying there are only three Black Metal bands: Burzum, Darkthrone and Mayhem. This may be a tad unfair considering important bands outside Norway like Sigh, Behemoth and Enthroned. Lastly, the argument has been made that Black Metal is a spiritual idea and not connected to music at all. These are all key debates when considering Black Metal and may take us away from the arguments of this essay. However, this essay was never to say that Dada and Black Metal are definitely connected but simply to show that looking at one may inform the other and offer a better understanding. If we assume that Black Metal is spiritual it may have a similar feeling to Dada – both were fiercely anti-society. Therefore its not too far to say that Black Metal is a passion that not all were ever meant to get and perhaps this is similar to Dada.

Bibliography

Artworks(Anti-artworks)

7 schizophrene Sonette (Hugo Ball, 1916)

ABCD (Raoul Hausmann, Collage, 1920)

Bicycle Wheel (Marcel Duchamp, Readymade, 1916-17)

The Coat-Stand (Port Monteau) (Man Ray, 1920)

Karawane (Hugo Ball, Performance, 1916)

L.H.O.O.Q. (Marcel Duchamp, Readymade, 1919)

Rrose Sélavy (Marcel Duchamp, 1921 (photograph by Man Ray))

The Fountain (Marcel Duchamp, Readymade, 1917)

Unhappy Readymade (Marcel Duchamp, Readymade, 1919)

Untitled Rayograph (Man Ray, Gelatin Silver Photogram, 1922)

Why Not Sneeze, Rose Sélavy? (Marcel Duchamp, Readymade, 1921)

Books

Ades, Dawn. ‘Dada and Surrealism’ in Stangos, Nikos (E). Concepts of Modern Art From Fauvism to Postmodernism. Thames & Hudson, UK, 1994 (Third Edition, 2003 Reprint).

Beste, Peter (a). Black Metal, Powerhouse Books, 2008.

Cabanne, Pierre (a). Dialogues with Marcel Duchamp. Da Capo Press, 1987.

Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005.

Duchamp, Marcel (a). Peterson, Elmer (E); Sanouillet, Michel (E). The Writings of Marcel Duchamp. Da Capo Press, 1989.

Hopkins, David (a). Dada and Surrealism: A Very Short Introduction. OUP Oxford, 2004.

Kuenzliy, Rudolf E. (a) Dada and Surrealist Film. MIT Press, 1996.

Moynihan, Michael; Soderlind, Didrik (a). Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Metal Underground, Feral House, US, 2003 (2nd Revised Edition).

Wilson, Scott (E). Melancology: Black Metal Theory and Ecology. Zero Books. UK, 2014.

Films/Documentaries

Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey. Dir. Sam Dunn, Scot McFadyen, Jessica Joy, Wise. Canada, 2005. DVD.

True Norwegian Black Metal VBS TV/Vice Magazine, 2007.

Internet Sources

Author Unknown, 2010. ‘Dio’s two-finger gesture – what does it mean?’ on

news.bbc.co.uk at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8687002.stm (last accessed 07/11/15)

Author Unknown. ‘Dada’ on translatekabyle.com at http://www.translatekabyle.com/en/dictionary-english-kabyle/Dada (29.11.15 Last accessed)

Author Unknown. ‘Emperor’ on users.globalnet.co.uk at http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~jasen01/warsongs/emperorinterview.htm (09/11/15 Last accessed)

crypticrock.com at http://crypticrock.com/interview-satyr-of-satyricon/ (29/11/15 Last accessed)

wikisource.org at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dada_Manifesto_(1916,_Hugo_Ball) (14/01/15 Last Modified, 29/11/15 Last accessed)

Guice, John. ‘Max Ernst’ on utopiadystopiawwi.wordpress.com at https://utopiadystopiawwi.wordpress.com/surrealism/max-ernst/ (09/11/15 Last accessed)

Huey, Steve. ‘Black Sabbath’ on allmusic.com at http://www.allmusic.com/album/black-sabbath-mw0000652046 (29/11/15 Last accessed)

Lahdenpera, Esa. ‘Northern Black Metal Legends’ on fmp666.com at http://www.fmp666.com/moonlight/mayhem.html (29/11/15 Last accessed)

Munkeby, Jørgen. ‘Less is Bore; The Ever Upward Spiral in Intensity’ on themonolith.com at http://www.themonolith.com/music/jorgen-munkeby-of-shining-less-is-bore-the-ever-upward-spiral-in-intensity/ (29/11/15 Last accessed)

O’Malley, Stephen (E). ‘Satyricon’ in Descent Magazine, 1995 on: Thor magnusson, Magnus. members.tripod.com at http://members.tripod.com/~black_metal/satyricon/descint.html (09/11/15 Last accessed)

Simms, Kelley. ‘Ihsahn – “The Black Metal Inner Circle Has Become a Very Special Media-Created Phenomenon”’ on bravewords.com at http://bravewords.com/news/ihsahn-the-black-metal-inner-circle-has-become-a-very-special-media-created-phenomenon (29/11/15 Last accessed)

Tzara, Tristan. ‘Dada Manifesto’ on 391.org at http://www.391.org/manifestos/19180323tristantzara_dadamanifesto.htm (29.11.15 Last accessed)

Troll (E). ‘Immortal’ on metalkings.com at http://metalkings.com/reviews/immortal/immortal.htm (29/11/15 Last accessed)

Vikernes, Varg. (Count Grishnakh) ‘A Burzum Story: Part I – The Origin and Meaning’ on Burzum.org at http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/a_burzum_story01.shtml (29.11.15 Last accessed)

Vikernes, Varg. (Count Grishnakh) ‘A Burzum Story: Part VI – The Music’ on burzum.org at http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/a_burzum_story06.shtml (29/11/15 Last accessed)

Vikernes, Varg. (Count Grishnackh) ‘A Review of M. Moynihan & D. Soderlind’s “Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Underground” (New Edition)’ on burzum.org at http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/lords_of_chaos_review.shtml (29.11.15 Last accessed))

Magazines

Brown, Louise (E). Terrorizer’s Secret History of Black Metal. Terrorizer Magazine, UK Sep 2009.

Picabia, Francis (E). 391. Magazine, Spain, 1917. (Issues 1-4).

Discography

A Blaze Under the Northern Sky (Darkthrone, Peaceville, 1992)

Antichrist (Gorgoroth, Malicious, 1994)

Aske (Burzum, Deathlike Silence, 1993)

Bathory (Bathory, Tyfon, 1984)

Battles in the North (Immortal, Osmose, 1995)

Black Metal (Venom, Neat, 1982)

Black Sabbath (Black Sabbath, Vertigo, 1970)

Bloodlust and Perversion (Carpathian Forest, Independent, 1992)

Burzum (Burzum, Deathlike Silence, 1992)

Dark Medieval Times (Satyricon, Moonfog, 1994)

Deathcrush (Mayhem, Posercorpse, 1987)

De Mysteriis Dom Sathanas (Mayhem, Deathlike Silence, 1994)

Destroyer (Gorgoroth, Nuclear Blast, 1998)

Det Som Engang Var (Burzum, Cymophane, 1993)

Diabolical Fullmoon Mysticism (Immortal, Osmose, 1992)

Emperor (Emperor, Candlelight, 1993)

Filosofem (Burzum, Misanthropy, 1996)

Grymyrk (Thorns, Independent, 1991)

Hvis Lyset Tar Oss (Burzum, Misanthropy, 1994)

In the Nightside Eclipse (Emperor, Candlelight, 1994)

Into the Woods of Belial (Thou Shalt Suffer, Independent, 1991)

Love it to Death (Alice Cooper, Straight, 1971)

Nemesis Divina (Satyricon, Moonfog, 1996)

Pure Fucking Armageddon (Mayhem, Funny Farm, 1986)

Pure Holocaust (Immortal, Osmose, 1993)

Scorn Defeat (Sigh, Deathlike Silence, 1993)

Sventevith (Storming Near the Baltic) (Behemoth, Pagan, 1995)

The Shadowthrone (Satyricon, Moonfog, 1994)

Towards the Skullthrone of Satan (Enthroned, Blackend, 1997)

Transilvanian Hunger (Darkthrone, Peaceville, 1994)

Under a Funeral Moon (Darkthrone, Peaceville, 1993)

Vikingligr Veldi (Enslaved, Deathlike Silence, 1994)

Wrath of the Tyrant (Emperor, Wild Rag, 1992)

[1]Author Unknown. ‘Dada’ on translatekabyle.com at http://www.translatekabyle.com/en/dictionary-english-kabyle/Dada (29.11.15 Last accessed)

[2]Tzara, Tristan. ‘Dada Manifesto’ on 391.org at http://www.391.org/manifestos/19180323tristantzara_dadamanifesto.htm (29.11.15 Last accessed)

[3]Molesworth, Helen (A). ‘Rrose Sélavy Goes Shopping’ in Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005: 184.

[4]…Ibid p184. Included an footnote that read: “The account closest to the semiotic conditions that I am tracing can be found in David Joselit’s work on Duchamp, see Infinite Regress: Marcel Duchamp 1910-1941 (Cambridge, Mass., 1998).

[5]Erdmute Wenzel White, The Magic Bishop: Hugo Ball, Dada Poet (Columbia, S.C., 1998), 106-107. as cited in Demos, T.J. (A) ‘Zurich Dada: Aesthetics of Exile’ in Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005: Pp 19.

[6]Cooper, Alice. in Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey. Dir. Sam Dunn, Scot McFadyen, Jessica Joy, Wise. Canada, 2005. DVD.

[7]Author Unknown, 2010. ‘Dio’s two-finger gesture – what does it mean?’ on news.bbc.co.uk at http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/8687002.stm (last accessed 07/11/15) Despite the exact origins of the gesture there is a recognisable association between the gesture and Satan.

[8]Huey, Steve. ‘Black Sabbath’ on allmusic.com at http://www.allmusic.com/album/black-sabbath-mw0000652046 (last accessed 29/11/15)

[9]Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey. Dir. Sam Dunn, Scot McFadyen, Jessica Joy, Wise. Canada, 2005. DVD.

[10]Munkeby, Jørgen. ‘Less is Bore; The Ever Upward Spiral in Intensity’ on themonolith.com at http://www.themonolith.com/music/jorgen-munkeby-of-shining-less-is-bore-the-ever-upward-spiral-in-intensity/ (Last accessed 29/11/15)

[11]Lahdenpera, Esa. Euronymous (In interview). ‘Northern Black Metal Legends’ on fmp666.com at http://www.fmp666.com/moonlight/mayhem.html (Last accessed 29/11/15)

[12]Arguments for and against elitism appear strong and is a huge subject in itself. Though we see some debate over some key bands being considered as Black Metal bands by Euronymous and Count Grishnackh in (…Ibid) an argument for originality can also be seen by Count Grishnackh “So in short Black Metal was all about originality and not sounding or being like anybody else.” (Vikernes, Varg. (Count Grishnackh) ‘A Review of M. Moynihan & D. Soderlind’s “Lords of Chaos: The Bloody Rise of the Satanic Underground” (New Edition)’ on burzum.org at http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/lords_of_chaos_review.shtml (29.11.15 Last Accessed)). This dualism of accepting and not accepting something or what something is or isn’t seems to appear frequently with regards to aspects of Black Metal. This is further touched upon in Masciandaro, Nicola and Irtenkauf, Dominik. ‘Black Metal Theory’ in Wilson, Scott (E). Melancology: Black Metal Theory and Ecology. Zero Books. UK, 2014.

[13]‘Black Metal Bad Boys’ in Brown, Louise (E). Terrorizer’s Secret History of Black Metal. Terrorizer Magazine, UK Sep 2009.

[14]…Ibid.

[15]…Ibid.

[16]…Ibid.

[17]Troll (E). Abbath in ‘Immortal’ on metalkings.com at http://metalkings.com/reviews/immortal/immortal.htm (Last accessed 29/11/15)

[18]O’Malley, Stephen (E). ‘Satyricon’ in Descent Magazine, 1995 on: Thor magnusson, Magnus. members.tripod.com at http://members.tripod.com/~black_metal/satyricon/descint.html (29/11/15 Last accessed)

[19]Author Unknown. Ihsahn in ‘Emperor’ on users.globalnet.co.uk at http://www.users.globalnet.co.uk/~jasen01/warsongs/emperorinterview.htm (29/11/15 Last accessed)

[20]Author Unknown. ‘Interview – Satyr of Satyricon’ on crypticrock.com at http://crypticrock.com/interview-satyr-of-satyricon/ (29/11/15)

[21]André Breton cited in Ades, Dawn. ‘Dada and Surrealism’ in Stangos, Nikos (E). Concepts of Modern Art From Fauvism to Postmodernism. Thames & Hudson, UK, 1994 (Third Edition, 2003 Reprint). Pp111.

[22] Gaahl in True Norweigen Black Metal. VBS TV/Vice Magazine, 2007.

[23]Ball, Hugo. ‘Dada Manifesto’ on wikisource.org at http://en.wikisource.org/wiki/Dada_Manifesto_(1916,_Hugo_Ball) (14/01/15 Last Modified, 29/11/15 Last accessed)

[24]Ades, Dawn. ‘Dada and Surrealism’ in Stangos, Nikos (E). Concepts of Modern Art From Fauvism to Postmodernism. Thames & Hudson, UK, 1994 (Third Edition, 2003 Reprint). Pp118.

[25]Ibid Pp 112.

[26]Vikernes, Varg. (Count Grishnackh) ‘A Burzum Story: Part 1 – The Origin and Meaning’ on burzum.org at http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/a_burzum_story01.shtml (last accessed 29/11/15)

[27]Simms, Kelley. ‘Ihsahn – “The Black Metal Inner Circle Has Become a Very Special Media-Created Phenomenon”’ on bravewords.com at http://bravewords.com/news/ihsahn-the-black-metal-inner-circle-has-become-a-very-special-media-created-phenomenon (29/11/15 Last accessed)

[28] Euronymous. ‘Mayhem’ in Beste, Peter (a). Black Metal, Powerhouse Books, 2008.

[29] Simms, Kelley. ‘Ihsahn – “The Black Metal Inner Circle Has Become a Very Special Media-Created Phenomenon”’ on bravewords.com at http://bravewords.com/news/ihsahn-the-black-metal-inner-circle-has-become-a-very-special-media-created-phenomenon (29/11/15 Last accessed)

[30] Vikernes, Varg. (Count Grishnakh) ‘A Burzum Story: Part VI – The Music’ on burzum.org at http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/a_burzum_story06.shtml (29/11/15 Last accessed)

[31]Heap, Jane (A). “Dada,” The Little Review 8, no. 2 (Spring 1922): 46 as referenced in ones, Amelia (A). ‘New York Dada: Beyond the Readymade’ in Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005: Pp 154.

[32]Jones, Amelia (A). ‘New York Dada: Beyond the Readymade’ in Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005: Pp 159.

[33]Fleckner, Uwe (A). ‘The Real Demolished by Trenchant Objectivity’ in Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005: Pp 66.

[34]Dmeos, T.J (A). ‘Zurich Dada: The Aesthetics of Exile’ in Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005: Pp 8.

[35] Vikernes, Varg.(Count Grishnakh) ‘A Burzum Story: Part I – The Origin and Meaning’ on Burzum.org at http://www.burzum.org/eng/library/a_burzum_story01.shtml (29.11.15 last accessed)

[36]Molesworth, Helen (A). ‘Rrose Sélavy Goes Shopping’ in Dickerman, Leah (E) and Witkovsky, Matthew S. (E) The Dada Seminars: CASVA Seminar Papers 1: CASVA Seminar Papers v. 1, Distributed Art Publishers, 2005: Pp 179-181.

[37] Gaahl in True Norweigen Black Metal. VBS TV/Vice Magazine, 2007.

Leave a Reply